It is little wonder the life of Hemi Pomara has attracted the attention of writers and film makers. Kidnapped in the early 1840s, passed from person to person, displayed in London and ultimately abandoned, it is a story of indigenous survival and resilience for our times.

Hemi has already been the basis for the character James Pōneke in New Zealand author Tina Makereti’s 2018 novel The Imaginary Lives of James Pōneke. And last week, celebrated New Zealand director Taika Waititi announced his production company Piki Films is adapting the book for the big screen – one of three forthcoming projects about colonisation with “indigenous voices at the centre”.

Until now, though, we have only been able to see Hemi’s young face in an embellished watercolour portrait made by the impresario artist George French Angas, or in a stiff woodcut reproduced in the Illustrated London News.

Drawing on the research for our forthcoming book, Empire, Early Photography and Spectacle: the global career of showman daguerreotypist J.W. Newland (Routledge, November 2020), we can now add the discovery of a previously unknown photograph of Hemi Pomara posing in London in 1846.

This remarkable daguerreotype shows a wistful young man, far from home, wearing the traditional korowai (cloak) of his chiefly rank. It was almost certainly made by Antoine Claudet, one of the most important figures in the history of early photography.

All the evidence now suggests the image is not only the oldest surviving photograph of Hemi, but also most probably the oldest surviving photographic portrait of any Māori person. Until now, a portrait of Caroline and Sarah Barrett taken around 1853 was thought to be the oldest such image.

For decades this unique image has sat unattributed in the National Library of Australia. It is now time to connect it with the other portraits of Hemi, his biography and the wider conversation about indigenous lives during the imperial age.

https://images.theconversation.com/files/344435/original/file-20200629-96659-13rvux8.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=770&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344435/original/file-20200629-96659-13rvux8.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=770&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344435/original/file-20200629-96659-13rvux8.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=967&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344435/original/file-20200629-96659-13rvux8.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=967&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344435/original/file-20200629-96659-13rvux8.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=967&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px" />

https://images.theconversation.com/files/344435/original/file-20200629-96659-13rvux8.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=770&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344435/original/file-20200629-96659-13rvux8.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=770&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344435/original/file-20200629-96659-13rvux8.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=967&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344435/original/file-20200629-96659-13rvux8.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=967&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344435/original/file-20200629-96659-13rvux8.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=967&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px" />

‘Hemi Pomare’, 1846, cased, colour applied, quarter-plate daguerreotype, likely the oldest surviving photographic image of a Māori. National Library of Australia

A boy abroad

Hemi Pomara led an extraordinary life. Born around 1830, he was the grandson of the chief Pomara from the remote Chatham Islands off the east coast of New Zealand. After his family was murdered during his childhood by an invading Māori group, Hemi was seized by a British trader who brought him to Sydney in the early 1840s and placed him in an English boarding school.

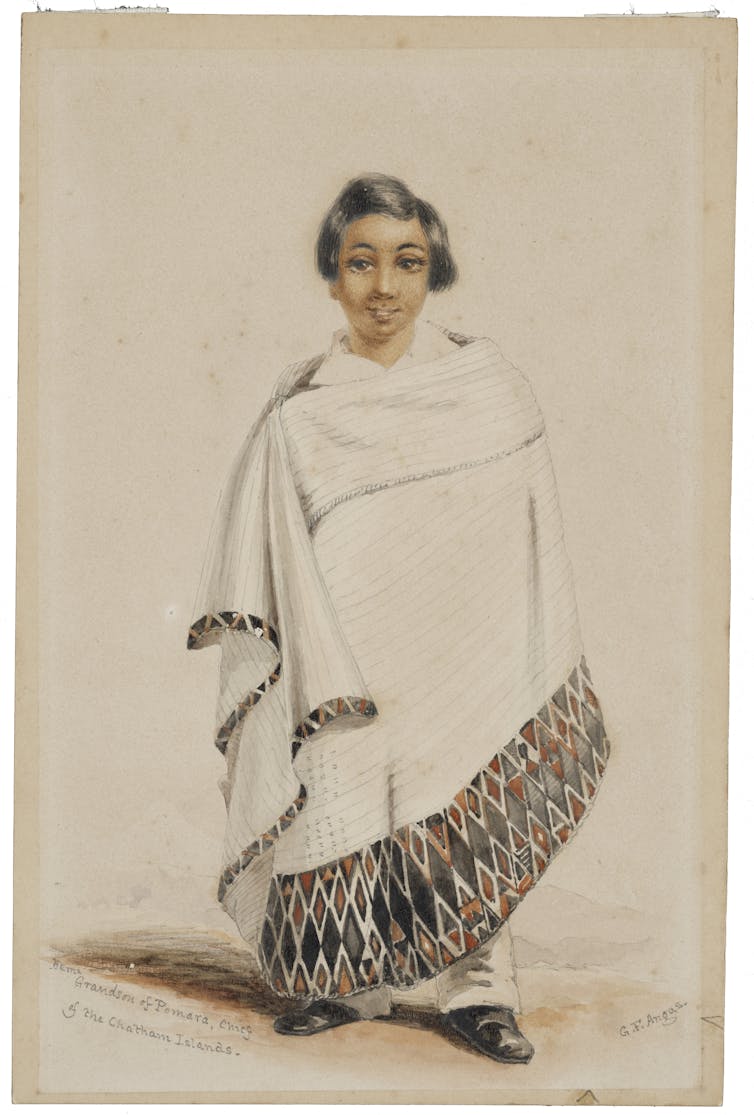

The British itinerant artist, George French Angas had travelled through New Zealand for three months in 1844, completing sketches and watercolours and plundering cultural artefacts. His next stop was Sydney where he encountered Hemi and took “guardianship” of him while giving illustrated lectures across New South Wales and South Australia.

Angas painted Hemi for the expanded version of this lecture series, Illustrations of the Natives and Scenery of Australia and New Zealand together with 300 portraits from life of the principal Chiefs, with their Families.

In this full-length depiction, the young man appears doe-eyed and cheerful. Hemi’s juvenile form is almost entirely shrouded in a white, elaborately trimmed korowai befitting his chiefly ancestry.

The collar of a white shirt, the cuffs of white pants and neat black shoes peak out from the otherwise enveloping garment. Hemi is portrayed as an idealised colonial subject, civilised yet innocent, regal yet complacent.

Read more: To build social cohesion, our screens need to show the same diversity of faces we see on the street

Angas travelled back to London in early 1846, taking with him his collection of artworks, plundered artefacts – and Hemi Pomara.

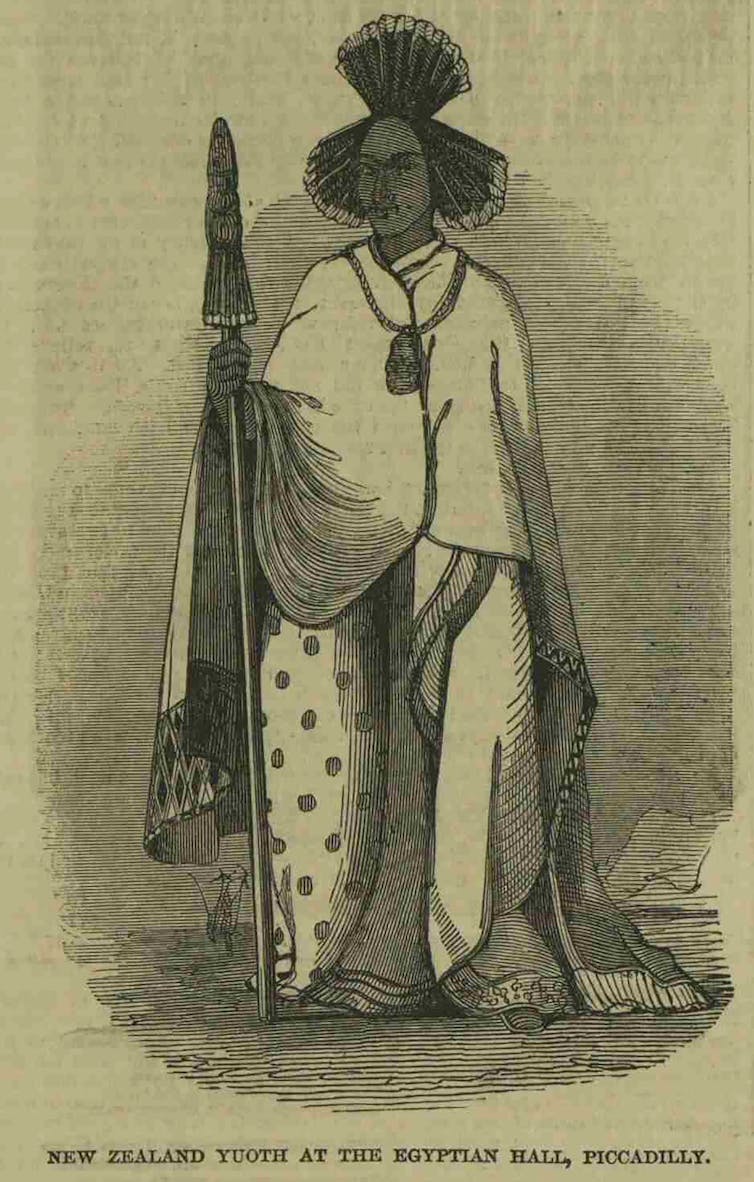

Hemi appeared at the British and Foreign Institution, followed by a private audience with Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. From April 1846, he was put on display in his chiefly attire as a living tableau in front of Angas’s watercolours and alongside ethnographic material at the Egyptian Hall, London.

The Egyptian Hall “exhibition” was applauded by the London Spectator as the “most interesting” of the season, and Hemi’s portrait was engraved for the Illustrated London News. Here the slightly older-looking Hemi appears with darkly shaded skin and stands stiffly with a ceremonial staff, a large ornamental tiki around his neck and an upright, feathered headdress.

https://images.theconversation.com/files/344666/original/file-20200629-155349-1k731kv.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=888&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344666/original/file-20200629-155349-1k731kv.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=888&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344666/original/file-20200629-155349-1k731kv.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=1115&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344666/original/file-20200629-155349-1k731kv.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=1115&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344666/original/file-20200629-155349-1k731kv.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=1115&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px" />

https://images.theconversation.com/files/344666/original/file-20200629-155349-1k731kv.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=888&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344666/original/file-20200629-155349-1k731kv.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=888&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344666/original/file-20200629-155349-1k731kv.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=1115&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344666/original/file-20200629-155349-1k731kv.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=1115&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344666/original/file-20200629-155349-1k731kv.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=1115&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px" />

An idealised colonial subject: George French Angas, ‘Hemi, grandson of Pomara, Chief of the Chatham Islands’, 1844-1846, watercolour. Alexander Turnbull Library

A photographic pioneer

Hemi was also presented at a Royal Society meeting which, as The Times recorded on April 6, was attended by scores of people including Charles Dickens, Charles Darwin, and the pioneering London-based French daguerreotypist Antoine Claudet.

It was around this time Claudet probably made the quarter-plate daguerreotype, expertly tinted with colour, of Hemi Pomara in costume.

The daguerreotype was purchased in the 1960s by the pioneering Australian photo historian and advocate for the National Library of Australia’s photography collections, Eric Keast Burke. Although digitised, it has only been partially catalogued and has evaded attribution until now.

Unusually for photographic portraits of this period, Hemi is shown standing full-length, allowing him to model all the features of his korowai. He poses amidst the accoutrements of a metropolitan portrait studio. However, the horizontal line running across the middle of the portrait suggests the daguerreotype was taken against a panelled wall rather than a studio backdrop, possibly at the Royal Society meeting.

Hemi has grown since Angas’s watercolour but the trim at the hem of the korowai is recognisable as the same garment worn in the earlier painting. Its speckled underside also reveals it as the one in the Illustrated London News engraving.

Hemi wears a kuru pounamu (greenstone ear pendant) of considerable value and again indicative of his chiefly status. He holds a patu onewa (short-handled weapon) close to his body and a feathered headdress fans out from underneath his hair.

We closely examined the delicate image, the polished silver plate on which it was photographically formed, and the leatherette case in which it was placed. The daguerreotype has been expertly colour-tinted to accentuate the embroidered edge of the korowai, in the same deep crimson shade it was coloured in Angas’s watercolour.

Read more: Director of science at Kew: it's time to decolonise botanical collections

The remainder of the korowai is subtly coloured with a tan tint. Hemi’s face and hands have a modest amount of skin tone colour applied. Very few practitioners outside Claudet’s studio would have tinted daguerreotypes to this level of realism during photography’s first decade.

Hallmarks stamped into the back of the plate show it was manufactured in England in the mid-1840s. The type of case and mat indicates it was unlikely to have been made by any other photographer in London at the time.

https://images.theconversation.com/files/344670/original/file-20200629-155322-my59r.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=941&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344670/original/file-20200629-155322-my59r.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=941&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344670/original/file-20200629-155322-my59r.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=1182&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344670/original/file-20200629-155322-my59r.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=1182&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344670/original/file-20200629-155322-my59r.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=1182&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px" />

https://images.theconversation.com/files/344670/original/file-20200629-155322-my59r.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=600&h=941&fit=crop&dpr=2 1200w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344670/original/file-20200629-155322-my59r.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=600&h=941&fit=crop&dpr=3 1800w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344670/original/file-20200629-155322-my59r.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=45&auto=format&w=754&h=1182&fit=crop&dpr=1 754w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344670/original/file-20200629-155322-my59r.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=30&auto=format&w=754&h=1182&fit=crop&dpr=2 1508w, https://images.theconversation.com/files/344670/original/file-20200629-155322-my59r.jpg?ixlib=rb-1.1.0&q=15&auto=format&w=754&h=1182&fit=crop&dpr=3 2262w" sizes="(min-width: 1466px) 754px, (max-width: 599px) 100vw, (min-width: 600px) 600px, 237px" />

‘New Zealand Youth at Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly’, wood engraving, The Illustrated London News, 18 April 1846.

Survival and resilience

After his brief period as a London “celebrity” Hemi went to sea on the Caleb Angas. He was shipwrecked at Barbados, and on his return aboard the Eliza assaulted by the first mate, who was tried when the ship returned to London. Hemi was transferred into the “care” of Lieutenant Governor Edward John Eyre who chaperoned him back to New Zealand by early December 1846.

Hemi’s story is harder to trace through the historical record after his return to Auckland in early 1847. It’s possible he returned to London as an older married man with his wife and child, and sat for a later carte de visite portrait. But the fact remains, by the age of eighteen he had already been the subject of a suite of colonial portraits made across media and continents.

With the recent urgent debates about how we remember our colonial past, and moves to reclaim indigenous histories, stories such as Hemi Pomara’s are enormously important. They make it clear that even at the height of colonial fetishisation, survival and cultural expression were possible and are still powerfully decipherable today.

For biographers, lives such as Hemi’s can only be excavated by deep and wide-ranging archival research. But much of Hemi’s story still evades official colonial records. As Taika Waititi’s film project suggests, the next layer of interpretation must be driven by indigenous voices.

Elisa deCourcy, Australian National University and Martyn Jolly, Australian National University

The authors would like to acknowledge the late Roger Blackley (Victoria University, Wellington), Chanel Clarke (Curator of the Maori collections, Auckland War Memorial Museum), Nat Williams (former Treasures Curator, National Library of Australia), Dr Philip Jones (Senior Curator, South Australian Museum) and Professor Geoffrey Batchen (Professorial chair of History of Art, University of Oxford) for their invaluable help with their research.

Elisa deCourcy, Australian Research Council DECRA Fellow 2020-2023, Research School of Humanities and the Arts, Australian National University, Australian National University and Martyn Jolly, Honorary Associate Professor, School of Art and Design, Research School of Humanities and the Arts, College of Arts and Social Sciences, Australian National University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Comments

Good morning Nicholas,

Thank you for taking the time to reply and I apologise for my own delay in getting back to you. Thank you also for explaining how to more effectively navigate Daguerreobase, I see your point now about the wider collection it captures, albeit none of the US material. This is understandable because Harry Ransom’s large collection of Claudets are undigitised.

I appreciate your fine-grained analysis of the curvature of the top-arch of the mat as being represented in the Beard collection, and I thank you for being so invested and thorough in this research, and for your kindness in sharing it with us. However, I cannot find any of examples from this selection with a narrow date range to the mid-1840s and many have a time window that begins as late as the early 1850s. The point I was trying to make in my discussion is that if you focus singularly on one aspect of the materiality, considering the small sample size of surviving images which we both agree on, you tend to lose a sense of the collective evidence from the object and its associated records. In this instance, for example, the colour tinting is of a much finer style than the Beards on Daguerreobase, which use a different palette and smaller section of colours. Like I said in my previous message, we also know of a meeting between Claudet and Hemi. We make some hypotheses about the wall panelling and furniture (which others below, on this thread, have commented on too), and consider it not to be taken in a typical studio setting. We have been contacted by another collector who also has an unstamped Claudet in a similar case, albeit with an unidentified subject (this discussions is evolving).

I apologise for the quality of the snaps I sent though, you're right they aren't helpful. They were taken hurriedly, under fluroescent lights in the National Library. The case is a deep maroon colour, with a veining finish, and with lighter maroon felt lining. I cannot confirm if it's leather or leatherette, I would want to double check. Martyn and I are still waiting to get back on-site at the Library amid current schedules and restrictions to reshot the images, which we will share with you.

With thanks,

Elisa

Good evening Elisa,

Yes, I am aware the sample sizes are small and represent a tiny proportion of the relevant photographer's output. In all I looked at almost 400 daguerreotypes. Fortunately I didn't draw any firm conclusions and have never claimed it as an 'authoritative sample'. Nevertheless the results were interesting enough to share and I hoped they might be useful.

My posting did not discuss 'likely authors from the UK' the intention was to simply see if Daguerreobase could help. I started with Ken Jacobson's list of photographers and looked at the mats on their daguerreotypes as represented on Daguerreobase. This was stated in my posting.

The statement, 'So it does not surprise me that you did not find an exact quarter-plate flat-topped with arched top-cornered mat to match exactly' misses the point. There were no mats on Claudet daguerreotypes in Daguerreobase with square lower corners and a flat top in any size. All the tops have gentle curves. In contrast, despite the small sample size there were a goodly selection of various flat tops in the Richard Beard listing. Yes, there is diversity in housings but there are also patterns which can be helpful.

Thank you for the link to the small plate in the Getty collection by Claudet with a flat top mount, albeit too small and of a different curvature.

Your comment about the NPG not featuring in Daguerreobase was puzzling as we included all the daguerreotypes that were in the National Portrait Gallery collection at the time. They have subsequently acquired one more Claudet daguerreotype, 'Sergeant Major in the Coldstream Guards' which I have now added to Daguerreobase.

Similarly the statement about the number of collections we included in Daguerreobase is inaccurate. Daguerreobase includes Claudet material from about twenty-five institutions in Europe and many more than just the two private collections. If you look at this webpage http://www.daguerreobase.org/en/collections?f_strings_creator%5B0%5... and then click on 'More' under 'Collection', you will see the various institutions and collectors listed alphabetically (45 in all, rather more than the four collections you claim).

Yes, US based collections are not included as Daguerreobase is a database of daguerreotypes and related material in the UK and continental Europe. The three institutions you list have some nice material but looking at the numbers of single plate daguerreotypes by Claudet, for example, does not produce a huge number.

Thank you for the images. On my screen (recently colour calibrated) the leather appears dark green, verging on black, in one image and purple in the other. May I ask which is closest to the correct colour? As you doubtlessly know, daguerreotype cases were made in both colours, though dark green is less common.

I have seen the 'veining' you describe on many daguerreotype cases. I understand it is called boarded leather (information from a very experienced leather specialist), see also https://www.leather-dictionary.com/index.php/Boarded_leather_-_Boar... . The term leatherette is also confusing as it means artificial leather. Is this what is intended?

I hope this is useful,

Nicholas Burnett

Hello Nicholas,

As the co-author of this piece, and indeed the book I am going to jump in and reply to a few of your thoughts.

Hemi is in London from March 1846 to early February 1847. This stay has an interruption in the middle from about June (the end of the Egyptian Hall season) to about October where Hemi is travelling to, and back from, the Barbados. We have already discussed why this image was not taken in Australia and New Zealand below. Any discussion of likely authors from the UK who are not operating between March 1846 and early February 1847 is not relevant to this particular image (i.e. Williams operating independently; Mayall, probably Kilburn too who has only about a 2 week cross-over in operation with Hemi’s stay).

Daguerreobase is a fantastic resource but your use of it for a critical mass study is tricky to draw conclusions from in a few key respects. 98 single-frame daguerreotypes from Claudet’s business as an authoritative sample are a tiny fraction of his output for a 14-year commercial career, as I’m sure you would agree. This is a fraction made tinier by where the database draws its Claudet sample from - two private collections, The National Media Museum, Bradford and the V&A (Royal Society collection). NPG, London doesn’t feature, neither do really substantial and significant American collections of Claudet (Harry Ransom; MET; Getty). So it does not surprise me that you did not find an exact quarter-plate flat-topped with arched top-cornered mat to match exactly. The Getty has a flat-topped with arched top-cornered mat daguerreotype ..., albeit a ninth plate.

What we do glimpse in Daguerrobase and in other collections is diversity: diversity in the radial curve of the arch on the top-side of the mat and mats' associated bevel cut. There is clearly a lot of variation in all aspects of the complete daguerreotype package.

Thanks for the Daguerreobase links to the Beard and Beard patentee works. Of the Beard patentees there are only two examples in this database with similar mats (one daguerreotype with colour applied and no indication of plate size, and one uncoloured). As you say, there are far more examples of flat-topped with arched top-cornered mats from Beard’s own studio but many of these are dated to a later time, the 1850s, well after Hemi has left. I note that none of the Beard’s with this mat are in a Morocco case that has a veining - rather than dappled - leatherette finish. See attached images. So it’s a medley of lining up the materiality.

This is an unusual image in many ways, for example Hemi is posed differently to most Europeans, standing full-length, which can primarily be explained by a desire to capture the extent of his ‘ceremonial’ costume, specifically the detail of his korowai. To us this feels like it was taken at the time of his Adelaide Galleries and Royal Society exhibition, when Hemi was posing in this dress, for ‘the season’ around April-June 1846. As you may have read, Claudet was in attendance at the April Royal Society meeting, hosted by the Marquees of Northampton at his Piccadilly terrace, where Hemi was ‘on display’ in his Egyptian Hall costume. So the two were at the same event, an event which would have been a good opportunity for Claudet to promote his business. (You can see the attendees, a who’s who of London, here: ‘The Royal Society’, The Times (London), 6 April 1846, 5.)

With thanks for your interest and engagement.

ElisaHemi%20case.jpg Hemi%20case%20II.jpeg

This is very interesting work and a stimulating discussion.

I found Ken Jacobson's comment on the unusual '‘flatness’ of the arched top of the mat' intriguing and set out to look for other examples on Daguerreobase, see http://www.daguerreobase.org/en/collections. Daguerreobase is an on-line database that brings together more than 16,000 British and European daguerreotypes. With such a large database it should be possible to find other examples of this unusual mat. Following the hypothesis that the portrait was taken in London, I looked at the listings of the main photographers as discussed by Ken.

Starting with Claudet, there are 98 single daguerreotypes listed (as well as many stereo daguerreotypes). None of these have the flat top to the mount. Also, the single portraits are usually taken either in front of a painted backdrop or alongside a plain curtain. The patterned curtains only seem to appear in his later stereoscopic daguerreotypes and, as already noted, Claudet's curtains are not an exact match.

Looking at the 140 single daguerreotypes by Kilburn does not show any mats with the flattened top.

We get the same result with the almost 60 plates listed as being by Mayall.

The database only has two daguerreotypes by Barratt but one does have a flattened top to the mat, albeit that the radius of the corners is rather less, see http://www.daguerreobase.org/en/collections/indeling/detail?f_strin...

The mat for this plate by TR Williams has the flattened top and a more gentle curve, see http://www.daguerreobase.org/en/collections/indeling/detail/start/6...

However, when we get to the listings for Richard Beard and Beard Patentee there are multiple examples, see http://www.daguerreobase.org/en/collections/indeling/grid/tmpl/inde... and http://www.daguerreobase.org/en/collections/indeling/grid?language=...

If you could post images of the housing it may be possible to find a match among the Beard daguerreotypes.

Best wishes,

Nicholas Burnett

Very interesting regarding the Marquess of Northampton. He inherited a spectacular collection, added to it and was deeply interested in art and science. The two portraits of him are by Scots (his wife was Scottish); a big oil by Henry Raeburn and a calotype by Hill and Adamson around 1844. Could it be the picture was taken in bath house Piccadilly (built 1823 dem. 1960)? Could it have been commissioned by him?

I think it unlikely a studio would have the same cloth covering for the furniture and the drape but that would be very likely in a house. You can imagine a photographer improvising with a chair and a curtain. This doesn't explain the flat background which is more like a studio. But I suspect this particular chair is not in the drawing room - more likely a smaller sitting room or bedroom.

There are pictures of the interior of Bath house in 1911, o the English heritage site but nothing relevant there.

Thanks Joe,

Yes, it's intriguing to speculate that it may perhaps have been taken at the Egyptian Hall with an Egyptian Revival chair! On the other hand they could just be generic studio accoutrements, their slightly improvised air may be because they come from from early on in the piece, 1846, rather than a few years later when most of the daguerreotypes we have online come from. We were led to this speculation by the reports of the Royal Society conversazione which was attended by Angas, Pomare in his costume and Claudet, it was at the Marquis of Northampton's Piccadilly mansion and: ‘The noble president’s saloon was crowded with models of new scientific inventions and works of arts, and the meeting was altogether of a very interesting character.’

Just to add to my previous comment, I am taken with Martyn Jolly's thought that the image may have been made in the Egyptian Hall. The armchair shown is a very simplified and later version of an Egyptian Revival form that became popular after the Napoleonic expedition. This is a very elaborate version but you can see the similarities. The armchair in the Hemi DAG does have some sort of decoration on the front legs but it is difficult to see.

I hope I am not repeating observations made by others but for what it is worth:

The drape and the chair covering appear to be the same cloth. The chair and especially the upholstery looks 'provincial' - not the very stylish French furniture and material evident in the Claudet images. I think it is also William IV in style and date (1830-45) so within the period you are suggesting for the image. It could have been taken later of course and this is more likely if it is indeed a provincial or a Pacific studio.

The background looks like a board, possible a moveable board, that does not quite touch the floor. In the Claudet images the background (which may also be a moveable screen) always seems to have a skirting board, making it look more like a room setting.

Joe Rock

There are a lot of Claudet dags in the RPS Collection and V&A Collections: a couple here look promisiing and a search pulls up other images which show chairs and drapes.

http://media.vam.ac.uk/collections/img/2009/BY/2009BY7232_2500.jpg

http://media.vam.ac.uk/collections/img/2009/BY/2009BY7606_2500.jpg

The crop was from this: https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/tinted-daguerreotyp...

Hi Michael,

Thanks for showing that Claudet detail, we agree that the floral patterns are very similar, although perhaps not identical. We also note the close similarity in colouring technique between the two images. Could you tell us a little bit more about that Claudet daguerreotype? While we are looking at details, we have been speculating on the horizontal wall panel behind Hemi Pomare, between the tip of his patu onewa (short-handled weapon) and the improvised curtain with the floral pattern, we have also been speculating on the geometric pattern of the floor covering. Although Claudet is the most likely origin for image, we have been wondering if perhaps the image was not exposed at his advertised establishment with its ‘desirable accommodations' ‘entered through the Adelaide Gallery’, but perhaps at a nearby location such as the Egyptian Hall or the Royal Society. We are interested in the extent of the porosity between the daguerreotype trade and other forms of scientific spectacle and rational entertainment. Any thoughts received with interest.

Hi Tony,

Thanks for that detailed documentation of Hemi's long voyage home and his Sydney stopover, that fills in some more details for us. The information regarding the interpreter Piri Kawau is also really interesting. Thanks for taking the trouble to fill us in.

-

1

-

2

of 2 Next